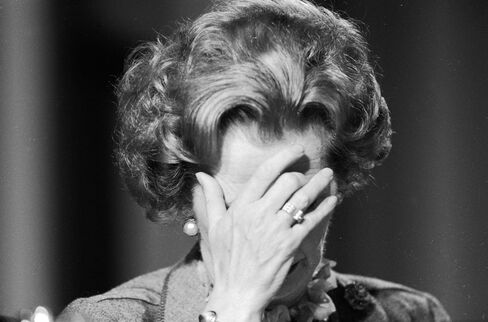

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at the 1985 Conservative Party Conference.

Photographer: Keystone/Getty Images

The great sweep of economic history is a series of “rises” and “falls”—from the fall of Rome to the rise of China. The intriguing episodes that spark the “what ifs” of history come lower down—when a medium-size power suddenly reverses an inevitable-seeming trajectory. That’s what Britain did under Margaret Thatcher and her successors: a crumbling country unexpectedly overturning years of genteel decline to become Europe’s most cosmopolitan liberal entrepôt. My fear is this revival ended on June 23, 2016.

I can remember when my version of liberal Britain was born: in a sauna in San Francisco in 1981. I was visiting from the U.K., traveling around America with George, another 18-year-old, on our “gap year” between school and university. We were staying with George’s elderly cousin Antony, who had fled high-tax Britain, having made a lot of money on chickens. He took us to have a sauna with his equally elderly neighbor, a small intense man called Milton. They asked George and me about Thatcher, and when they discovered that we knew little, Milton took center stage, explaining how the prime minister, who took office in 1979, would break the unions, open up the economy, and transform Britain into a free-market exemplar.

George and I had no economics, but even we knew this was codswallop. Thatcher already looked in trouble: There were riots back home. The Britain we had grown up in was a class-ridden land of inevitable decline—sometimes benign (watching Upstairs, Downstairs), sometimes humiliating (being bailed out by the IMF), and sometimes uncomfortable (being taught by candlelight during the miners’ strikes). But the trajectory, pretty much since 1913, had been gradually downhill. Culturally, Britain could be cool—we had produced Mick Jagger and Monty Python. But economically we were finished. Later in my gap year, I watched the Grateful Dead and found them less hallucinogenic than the dreams of mad old Milton in that sauna.

When I returned to Britain, however, Milton Friedman was everywhere—the economist behind Thatcher’s free-market gamble. Sir Antony Fisher (as he later became) was less well-known, but he’s now celebrated as one of the great sponsors of the libertarian right. And what they forecast was basically correct; the trajectory of Britain did change.

You can argue that Thatcher was needlessly ruthless: Even today, many of the areas that voted for Brexit were in the industrial north that collapsed under her onslaught. You can claim she was an accident: Nobody in 1979 voted for “Thatcherism”; to most voters she seemed like a tough-minded pragmatist rather than an ideologue. You can say she was lucky: Had Argentina not invaded the Falklands in 1982, she might well have been a one-term prime minister. But the narrative changed—away from decline toward something more expansive, meritocratic, and confident.

Thatcher may have called herself a Conservative, but her inspiration was the classical liberalism of John Stuart Mill and Adam Smith, centered on free commerce and individual freedom and what we now call globalization. It sat at the heart of the first great Victorian age of globalization, which came to an end in 1914. For Thatcher these ideas were channeled through thinkers like Friedman. She wasn’t always as idealistic as she claimed, but the direction she set—and John Major and Tony Blair followed—was clearly toward open markets.

As a result, Britain has arguably been the big Western economy most comfortable with the current age of globalization. Not as successful as the U.S., to be sure. But we have usually been stauncher supporters of free trade and more at ease with foreigners buying our companies or running them, with privatizing government services, with the move from manufacturing to services, especially finance, and with foreigners playing for our football clubs or taking over our cuisine. And alongside that has grown a laissez-faire attitude toward individual freedom, from gay marriage to stem cell research.

This liberal Britain didn’t always work out well. Overreliance on finance meant we were especially exposed to the crunch in 2008. Even if in practice we were good at dealing with immigrants, there was still grumbling about foreigners, whether poor ones taking council houses or rich ones buying up Chelsea. We’ve been schizophrenic toward the European Union: We liked the single market but hated its tangle of regulation.

Yet this love-hate relationship has served Britain very well. The fact that we were at the free-market end of a sclerotic union increased our relative attractiveness. London has become the commercial capital of Europe and its talent magnet. Britain’s soft power has not been greater for decades.

What went wrong? The obvious rejoinder is liberal Britain worked a lot better for some Britons than for others. That is true. Many Brexiters also felt that they had been lied to repeatedly about immigration. Others see the EU as a doomed project—and think we are best out of it. Add in shameless political opportunism, a Euroskeptic press that told voters there was no cost to voting Leave, and polls that showed Remain was in the lead (so a protest vote was just that), and you get to 52 percent of the electorate.

The chaos could pan out in a liberal direction. A few Brexiters believe they are Thatcher’s heirs, rejecting the EU leviathan. But most of the Leave voters want less globalization, not more. And Europe is hardly in a mood to give special favors to perfidious Albion. The revolt against the age of globalization could well spread. In terms of soft power, Britain’s reputation as a tolerant, stable haven is being shredded, day by day.

Hence the fear that the years 1979 to 2016 will be seen as the great exception—a brief revival in the centurylong decline of a former Great Power. By 2050 historians may well deem it inevitable that the financial capital of Europe would move to Germany. One irony is there was as much accident in the end of liberal Britain as there was in its founding. If few Britons knew what they were getting in Thatcher, perhaps fewer thought through the consequences of Brexit. They just wanted to give their politicians a kicking, believing it was risk-free. A lot depends on how quickly they admit they were wrong.

Micklethwait is editor-in-chief of Bloomberg.