Defeating the U.K. in negotiations will be easy. Dealing with inflamed anti-Europe sentiment won’t.

Be careful what you wish for, Mr. Barnier.

Photographer: John Thys/AFP/Getty Images

There were a few “Amens” coming from the U.K. after Italy’s far-right deputy prime minister, Matteo Salvini, reportedly told The Sunday Timesthat “there is no objectivity or good faith from the European side” when it comes to the bargaining over the terms of the U.K.’s exit from the European Union. He urged U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May to hold out for a better deal and prepare to walk away.

Salvini represents a populist euroskeptic party, hardly a mainstream European voice. And yet his words were music to the ears of those who suspect that the EU is out to swindle Britain as it negotiates to leave the bloc, and those who welcome any crack in the EU’s united front, no matter how small, as a sign they can still get their way.

There are two kinds of hardline Brexiters now. One is hopeful but deluded, the other realistic but destructive. The hopefuls argue that while the EU stayed united when it came to talking about the divorce payment or EU citizens’ rights, once the talk turns to car sales and the intricacies of supply chains, the different economic and political interests of member countries will assert themselves and a deal will be possible.

There is, in fact, almost no chance of the EU’s united front crumbling now. Chief EU negotiator Michel Barnier poured buckets of cold water on May’s post-Brexit trading proposal, increasing the likelihood that there will be no deal at all, never mind a cake-eating one.

Barnier may have seemed more conciliatory lately when it comes to access for London’s financial services industry. But he hasn’t conceded anything, really; London will be treated like New York and other financial centers, which gain access only once the EU has certified the “equivalence” of their regulatory systems to the EU’s. That’s a long way from the U.K.’s demands for “mutual recognition” of each other’s independently drafted rules.

The EU’s clear preference is to conclude a withdrawal treaty that paves the way for a transition period and a new negotiated trade relationship. But its bigger goals are preserving the unity of the bloc, the integrity of the single market and the sanctity of the 1998 Good Friday agreement that brought peace to Northern Ireland.

While the U.K. could help motivate talks by offering more payments into EU coffers (something Brexiters would find anathema) or a more generous deal for EU migrants, none of these things are tradable against the market access the U.K. wants. Financial services are important, but the industry is not the carrot, or the stick, that Brexiters once assumed.

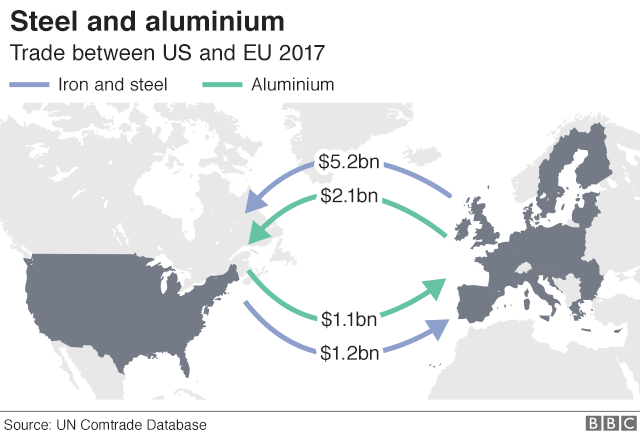

In terms of trade, it is true that the EU stands to lose from a no-deal Brexit; the U.K. is its most important trading partner. But the hit to individual EU countries is much less than the hit to the U.K. A study last year calculated the share of gross domestic product of each EU country tied up in trade flows with the U.K., and vice versa; only Ireland comes close to what Britain has at stake (10 percent of its GDP is tied up in trade flows with Britain).

The EU is happy to prove the deluded hopefuls wrong and drive the hard bargain it has always intended. But it’s the other group of Brexiters it should worry about more.

They’re the ones who have taken accurate stock of the EU arsenal and the U.K. political terrain. They are resigned to retreating, but prefer to blow up everything along the way. They’ll take a no-deal Brexit over May’s compromise plan any day. Their goal is now to make sure that the blame falls on the EU, May, the Remainers and anyone other than those who voted for Brexit. They plan to rally the resentful at the next election.

British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt alluded to this last week when he told a German audience that the approach being pursued by EU negotiators risks a no-deal Brexit happening “by accident,” and that this would “change British public attitudes to Europe for a generation.”

Salvini, too, knows the power of anti-EU sentiment. But does Barnier, a former French foreign minister and pan-European enthusiast? In seeking to extract more than the U.K. can reasonably give for gains the EU doesn’t really need, the EU risks triggering a collapse in negotiations for which it will share the blame. Barnier may have a plan to defeat the deluded hopefuls, but if he doesn’t help get a deal, he risks entrenching anti-EU sentiment even further.

To be fair, he doesn’t have much operating room — EU members and the European Parliament still need to approve the final withdrawal agreement. But the EU has long experience in creative fudging when principles and rules clash with political reality. Just ask any country that has violated EU rules on fiscal discipline.

What could Barnier do? He could signal a willingness to give the U.K. more time to negotiate by extending the two-year deadline that makes the divorce official on March 29, 2019. He could work toward an alternative solution to the fiendishly tricky Irish border problem (there are no easy or perfect solutions, but there are ideas with legs). He could at least work with May to modify her plan for a free-trade area for goods.

The withdrawal agreement is 80 percent concluded; the remaining 20 percent should be doable. But even if the end result isn’t an agreement, Barnier’s bigger goal should be to show British voters, and more importantly all euroskeptics, that the EU makes a good-faith effort to win their trust and their trade. The rest is up to them.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners