The dollar is in the midst of its strongest rally since 1984 and -- unlike then -- there may be little anyone can do to stop it.

Thirty years ago this month, the U.S. was powerful enough to muscle its way out of a damaging trade imbalance when it took financial markets by surprise with the Plaza Accord. In that agreement, it persuaded Japan, Germany, France and the U.K. to join in coordinated action to help weaken the dollar.

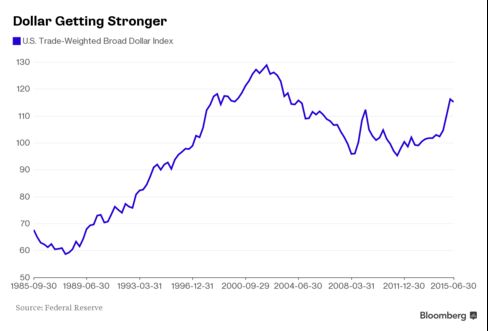

Now, the Federal Reserve’s willingness to raise its interest-rate benchmark, along with currency-weakening stimulus from other central banks, has strengthened the dollar enough to risk crimping U.S. inflation and casting a cloud over corporate earnings. The greenback is already within 8 percent of a record high, according to the Fed’s Trade-Weighted Broad Dollar Index, and the danger is tighter monetary policy may supercharge its rally.

“The Fed is in a position to raise rates but it is extremely cautious, and the impact of the one-way dollar strength on U.S. exporters and repatriated income must be taken into account,” said Makoto Utsumi, 81, who was a minister at the Japanese embassy in Washington D.C. at the time of the Plaza Accord and is now chairman of the global advisory board for Tokai Tokyo Financial Holdings Inc. “The common understanding for the need for policy cooperation shared at the Plaza Accord is lost and it’s not clear where the true leadership is in each country or in the world.”

The dollar has surged 20 percent against the yen in the past two years and 17 percent versus the euro as the prospect of higher U.S. interest rates contrasts with monetary easing in Japan and Europe. The Fed’s dollar index, which tracks the greenback versus 26 currencies of U.S. trading partners, has climbed more than 18 percent since the end of 2013, approaching the record high set in February 2002. It is heading for its steepest two-year advance since 1984, which saw it surge 32 percent.

At the same time, the International Monetary Fund flagged in its annual report in July that global imbalances were a hindrance to global growth and the dollar was trading “modestly above” a level consistent with its fundamentals.

Yet a Group of 20 gathering in Turkey this month ended without any concrete policy on how to respond to a slowing Chinese economy, even after an unexpected yuan devaluation fueled concern a currency war will derail global growth.

That’s a contrast with the September 1985 gathering of international finance ministers at the Plaza Hotel in New York. From 1979, the dollar had strengthened for six straightyears, making U.S. companies uncompetitive. On the 22nd, they signed an agreement to weaken the greenback, which subsequently tumbled about 50 percent against the yen in two years and 30 percent against the deutsche mark.

Human Relationships

The G-20 outcome highlights the loss of coordination since the 1980s that can only be built up through human relationships developed over years of regular contact, according to Japan’s former top currency official Toyoo Gyohten, who was involved in negotiations leading up to the Plaza Accord.

“It’s worrying that there now seems to be no venue to exchange views for crisis prevention preceding crisis management, which is extremely important,” he said. “An absence of an effective cooperation scheme will immediately transform a crisis in one country into a global crisis.”

The G-20 meetings are less likely to result in co-ordinated action in the major currency markets as it is harder to reach consensus among such a large group, said Mansoor Mohi-uddin, a senior markets strategist at Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc in Singapore.

“Plaza showed that co-ordinated action could help reverse the underlying trend of the currency markets -- provided it was in line with prevailing changes in interest-rate differentials,” he said. “The appetite for coordinated action in currency markets has waned over the last 30 years as turnover in global exchange-rate markets has increased sharply.”

Some Capacity

Meetings of the Group of Seven are now the most likely forum for future coordinated action in currency markets, Mohi-uddin said. G-7 action to support the euro in 2000 and weaken the yen after Japan’s earthquake in 2011 shows there is still some capacity for intervening in currency markets when trading becomes disorderly, he said.

In the meantime, the Fed’s isolation may add to pressure on it to keep interest rates lower for longer and protect the U.S. economy. In the past month, traders have pared bets the Fed will boost rates at its Sept. 16-17 meeting to a 28 percent chance of a rate increase, down from 50 percent odds as recently as Aug. 13.

“It is difficult to conduct coordinated intervention and macro-economic policy cooperation now,” said Tomomitsu Oba, who was Japan’s top currency official at the Plaza Accord talks, during a speech at the National Press Club in Tokyo on Monday. “Back in 1985, the Group of Five accounted for more than 50 percent of the world’s gross domestic product. Now, the world’s GDP is about $113 trillion, of which the G-7 totals about $34 trillion.”

by Chikako Mogi and Shigeki Nozawa

No comments:

Post a Comment