Switzerland is offering a stark lesson for the British politicians tasked with negotiating Brexit: the nation they admired for guarding its sovereignty within Europe has all but thrown in the towel.

More than two years after the Swiss electorate voted to limit immigration by European Union nationals, lawmakers last month sidestepped implementing curbs that threatened an economically vital set of treaties with Brussels. Instead, they backed a “light” proposal that merely stipulates job vacancies are advertised first in Swiss unemployment centers.

“It’s a complete fig leaf, as it won’t make any difference to the flow of EU citizens into the Swiss economy,” said Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, senior fellow at the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics. “It does what it’s supposed to do, which is not to have any changes.”

While Kirkegaard expects the EU to respond favorably to Swiss realpolitik, even the diluted plan for implementing the 2014 plebiscite isn’t a done deal as Brussels and Bern haggle over the fine print. When European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker meets Swiss President Johann Schneider-Ammann in Brussels on Oct. 28, the EU will be keen to avoid any concessions that could set a precedent for upcoming Brexit negotiations with the U.K.

If that solution falls apart, Switzerland also has a potential Plan B to ensure the economy doesn’t suffer a projected 32 billion-franc ($32.4 billion) a year shock from the cancellation of treaties covering everything from aviation to agriculture. The government will respond by the end of this month to recommend if voters should back or reject the so-called Rasa initiative that would annul the previous referendum on immigration.

The preference among key U.K. negotiators -- Brexit Secretary David Davis, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson and trade chief Liam Fox -- for a so-called hard Brexit that prioritizes immigration controls over access to the 28-nation bloc’s single market will make it difficult for the U.K. to match Swiss pragmatism, according to Rene Schwok, director of the Global Studies Institute at the University of Geneva.

“They’re not well known for their diplomacy, but perhaps they can adapt,” said Schwok. “The lesson is that Switzerland gave up. It’s been the history of Switzerland for centuries; you make concessions to stronger neighbors.”

U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May, who is fond of holidaying in the Swiss Alps, has said Switzerland won’t be the U.K.’s post-Brexit model.

“May clearly defines Brexit as having more controls on immigration and the Swiss proposal is the opposite,” said Kirkegaard. “If she doesn’t deliver a hard Brexit, then she will be assailed as a sellout.”

Referendum Dilemma

When Johnson called for the creation of “Britzerland” as an outer tier of the EU four years ago, he was admiring the deal negotiated in the 1990s under which Switzerland gained market access while retaining a degree of sovereignty. Crucially, it also allowed EU citizens to take up jobs and reside in the country without a special permit.

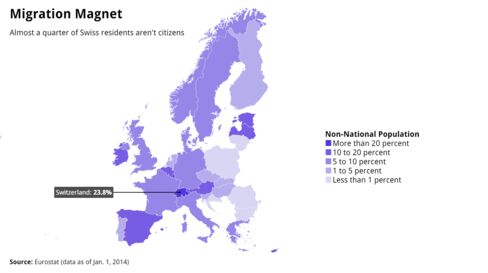

That looked like it would change when the anti-immigration Swiss People’s Party, or SVP, sponsored a measure to impose quotas on EU nationals. It passed by fewer than 20,000 votes in February 2014.

With formal EU-Swiss talks failing to produce a settlement, lawmakers sought to end the impasse by voting on Sept. 21 to implement the referendum without imposing immigration quotas or national preference.

While the SVP lambasted the proposal, the partial implementation of plebiscites has a long history in Switzerland, according to Georg Lutz, a professor of political science at the University of Lausanne. One example was the Alpine Initiative to curb heavy truck traffic in the Alps.

Unilateral Solution

“The lawmakers found a unilateral solution because negotiating a deal with the EU would have been impossible,” said Lutz. “For the U.K. renegotiating an exit, it’s much harder to find a win-win situation because there isn’t much to gain, but a lot to lose.”

To be sure, the proposal faces EU scrutiny that could thwart it. Mina Andreeva, a spokeswoman for the bloc’s executive arm in Brussels, said any solution must be implemented “in a way that respects obligations under the free-movement agreement.” Tages-Anzeiger reported last week the EU had concerns about a passage in the proposal that would allow Switzerland to take additional steps to control immigration if the stream of newcomers increases.

Still, Juncker talked of a “Swiss-specific” solution when he visited Zurich last month and the Tages-Anzeiger report said EU ambassadors in Brussels don’t object “in principle” to the implementation plan.

Andreas Auer, a former law professor at the universities of Zurich and Geneva, isn’t taking any chances. He has helped collect the requisite 100,000 signatures for another vote to annul the immigration referendum.

“We have direct democracy and people have the right to review their own decisions at any time,” said Auer, noting that Swiss universities have already been locked out of EU research programs because of the immigration vote.

The U.K. could also have a second referendum if the government “makes a hash of Brexit” and the economy deteriorates, said the Peterson Institute’s Kirkegaard. The Swiss experience shows the EU is guided more by politics than economic considerations, he said.

“There are often no overlaps between what national politics wants and allows and what the EU wants and allows,” according to Anand Menon, a professor of European Politics and Foreign Affairs at King’s College London. “There won’t be a deal to have your cake and eat it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment