Johan Carlstrom

Magdalena Andersson.

Photographer: Lisi Niesner/Bloomberg

High taxes, strong unions and an equal distribution of wealth.

That’s the recipe for success in a globalized world, according to Magdalena Andersson, the Social Democratic economist who’s also Sweden’s finance minister.

The 50-year-old has been raising taxes and spending more on welfare since winning power in 2014. She’s also overseen an economic boom, with Swedish growth rates topping 4 percent early last year, that has turned budget deficits into surpluses.

In a world still flinching from the financial crisis that hit a decade ago and the populist wave that followed, Sweden’s economic stewardship holds lessons that challenge the conventional wisdom in the U.S. on how taxes work, according to the Harvard-educated minister. Speaking in an interview in Stockholm, Andersson says success comes down to “three things: It’s the jobs, it’s our welfare and it’s our redistribution.”

It’s the polar opposite of the policy being developed across the Atlantic, where U.S. President Donald Trump is hoping tax cuts, less regulation and new trade deals will produce 3 percent growth within two years. Meanwhile, in Europe, the Nordic model is attracting attention. Emmanuel Macron, who on Sunday defeated Front National’s Marine Le Pen in the French presidential election, has urged his country to look north for ideas on how to organize a society.

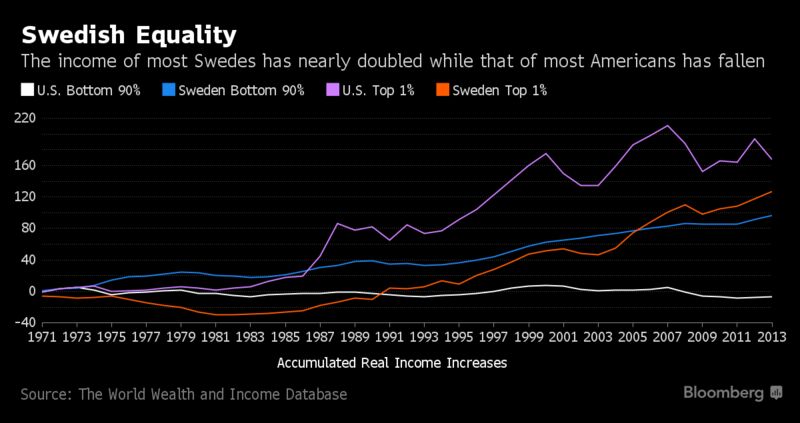

Andersson, who lists health care and education, “regardless of how much you earn,” as key to running a successful economy, points to income redistribution as the shield that can keep populist shocks at bay.

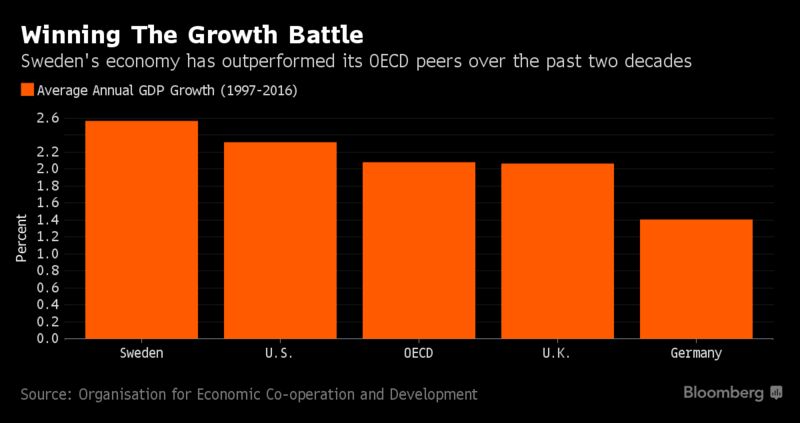

The numbers are compelling. Sweden has one of the world’s highest tax burdens, with tax revenue about 43 percent of GDP, according to OECDdata. The equivalent figure for the U.S. is about 26 percent. Sweden’s economy has grown almost twice as fast as America’s, expanding 3.1 percent last year, compared with 1.6 percent in the U.S.

Sweden has the highest labor force participation in the European Union. Andersson attributes this to tax-funded parental leave and affordable daycare, which make it easier for both parents to work.

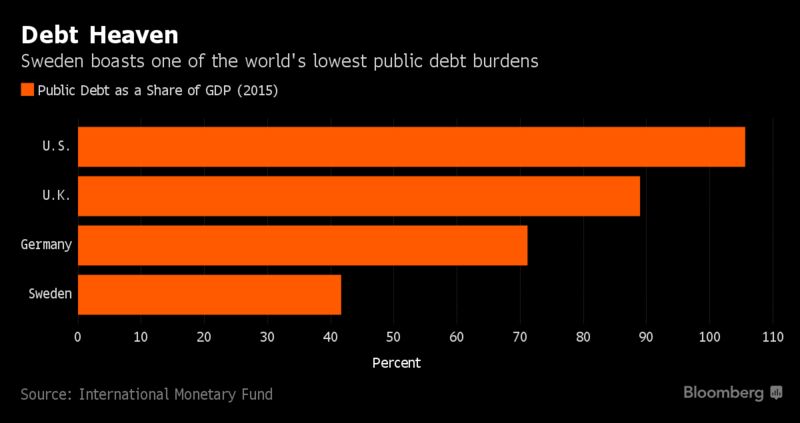

In contrast to most of its European peers, Sweden has budget surpluses. The EU average will be a shortfall of 1.6 percent in 2018, while the estimated deficit in the U.S. of 5.7 percent of GDP, EU Commission data published in February show.

The country also takes a pragmatic view of capitalism, which includes allowing businesses to fail if they can’t compete. Part of this includes providing a safety net and training for workers, features that Andersson says are crucial to keeping a dangerous anti-globalization sentiment at bay.

“In Sweden, it’s accepted that society changes and that some companies expand while others shrink, but that’s based on the fact that there are bridges from the old to the new jobs,” she said. “It’s important to have security during that change, both in the form a well-functioning unemployment insurance, but also active labor market policies.”

But not all Swedes are persuaded that more tax increases will help. Andersson faces a vote of no confidence from the opposition if she presents further hikes. Meanwhile, parts of corporate Sweden are rebelling. There are also numerical signs that the tipping point may have been reached, as GDP slows.

Sweden’s government has started tapping its surpluses to raise spending on everything from health care to education to defense and a stronger police presence. With an election looming next year, the Social Democratic-led administration is contending with its own right-wing nationalists, who have gained followers in the wake of record refugee inflows.

The center-right coalition that preceded the current government spent most of its eight years in power cutting taxes. They argue that Andersson and her boss, Prime Minister Stefan Lofven, are now putting economic gains at risk, and warn that generous benefits discourage people from working. The opposition also notes that Sweden has fallen behind in wealth per capita since taxes were raised in the 1970s, culminating in an economic crisis in the early 1990s when taxes as a share of GDP exceeded 50 percent.

According to the website Ekonomifakta, which is run by Sweden’s largest employer organization, the highest marginal tax rate has again crept up, reaching about 70 percent, including payroll taxes. With that in mind, the opposition is threatening a vote of no confidence against Andersson this autumn unless she withdraws her tax plan.

Banks and Sweden’s private equity industry have railed against the tax environment, with Scandinavia’s biggest financial group, Nordea Bank AB, threatening to leave. And a vibrant startup scene, led by music-streaming service Spotify Ltd., is calling for changes in how options-based income is taxed in an effort to attract more talent.

Andersson acknowledges there are limits, saying there’s no need for “big” tax increases in the coming years.

“They of course have negative effects,” she said. “All taxes do, but what you use the money for can have positive effects and that’s exactly what the Swedish model shows. You can have high taxes and high employment and growth.”

No comments:

Post a Comment