MASSENA, New York/JACKSON HOLE, Wyoming (Reuters) - After a turbulent year of anti-globalization backlash, central bankers still argue open borders and free trade are the key to more jobs, growth and prosperity.

But when they meet for the U.S. Federal Reserve's annual research conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, this week, it will be with the growing recognition that the world economic order they helped create could unravel unless the benefits of globalization can reach those left behind.

That means addressing the concerns of people like Grace Paige, a grandmother of seven from the struggling St. Lawrence County in northern New York state.

When Donald Trump promised to revive "middle America" by rolling back decades of globalization, Paige decided to give him a chance. The otherwise dependable Democratic voter sat out the election, contributing to the county's swing from a 57-percent majority for Barack Obama in 2012 to a 51-percent vote for Trump's economic nationalism.

"My grandkids need jobs," she said, counting out the ways her county has been abandoned over the last decade with the shuttering of a General Motors (

GM.N) car factory, an aluminum plant, and the Sears (

SHLD.O) department store where Paige once worked.

Central bankers reject Trump's economic nationalism, including renewed threats to tear up the 23-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement, if it leads to more protectionism.

But officials at the Fed in particular have in recent months broadened their policy debates to include issues such as racial disparities in labor markets or the fate of geographically or technologically isolated communities in an economy that is in many ways doing well.

"Frankly as economists ... we haven't probably paid enough attention to the transfer from one economy, where you aren't as globalized, to another," Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland President Loretta Mester told Reuters ahead of the Aug. 24-26 international gathering dedicated to securing global growth.

"Globalization and technological change is here to stay. And the promise of those is very good - we know that it can raise standards of living," Mester said. "It's just how do you make sure that it's distributed in a way so that the majority of people benefit."

Policymakers acknowledge, however, that there is no quick and easy way to help those whose jobs were moved overseas or were replaced by software and robots, or to tackle the political challenge that poses.

HALF-URBAN, HALF-RURAL, ALL TRUMP

A Reuters analysis of U.S. voting, jobs and demographic data shows that it was in areas like St. Lawrence - neither clearly in the orbit of the globally-connected cities that drive economic growth, nor fully rural - that were key to Trump's success.

They represent about a third of the roughly 3,100 counties in the continental United States and around 12 percent of the U.S. population, according to census data. Trump outperformed the 2012 Republican candidate Mitt Romney the most in those counties, which proved vital to his triumph in key swing states.

St. Lawrence - with its smattering of dairy-farm villages, college towns, and shuttered industrial sites - was also among 63 counties where votes swung by 10 percentage points or more to Trump from Obama.

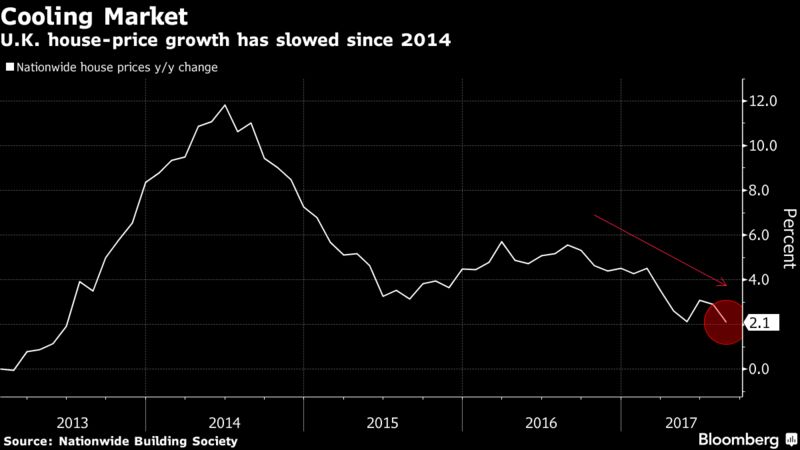

Similarly, areas of Britain on the edges of big cities had an outsized effect on the narrow June 2016 vote to leave the European Union.

Recognizing the challenge, Fed Governor Lael Brainard has made at least 10 visits from Appalachia to Mississippi studying why communities get left behind, extensive travel for a Fed governor outside the usual circuit of civic club and university speeches.

"We really do have to be focused on the kinds of policies that can reconnect those people to the workforce," Brainard said in a recent speech.

Monetary policy geared to an entire economy is ill suited to fix such problems, but the Fed's regional role in community development, as well as the bully pulpit shared by its policymakers, have prompted them to focus on possible options.

For example, in a trip to El Paso, Texas, Brainard explored how the Fed’s bank oversight and interest rate policy might improve financing for basic infrastructure and job training, according to regional Fed staff who helped arrange the tour.

At the regional level, Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari in January set up a research institute on income inequality, and said recently that social considerations in part led him to want to pause on raising interest rates.

“If we can keep people from being lost permanently, boy that’s a real positive for society," Kashkari said.

MONTREAL SUBURB

The diverging fortunes of St. Lawrence and nearby Clinton County, which shares a similar demographic profile, show how often factors such as location can make all the difference, and how hard they are to overcome.

Clinton County, which backed Democrat Hillary Clinton in 2016, shares a transportation corridor with Montreal, Canada's second-largest city in the neighboring Quebec province, allowing it to reap the benefits of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

"Our business is to make Quebec successful, to help Quebec with its exports. Now there's a novel idea," Garry Douglas, president of the North Country Chamber of Commerce, said in June of the NAFTA renegotiation talks at a forum in Plattsburg attended by New York Fed President William Dudley.

Plattsburg, Clinton County's hub, bills itself as "Montreal's U.S. Suburb," 15 percent of the county's residents work for subsidiaries of Canadian firms such as Bombardier (

BBDb.TO), and more than $1.5 billion flows south across the border in annual investment.

Only 35 miles (56 km) east lies St. Lawrence. With less convenient road, rail and air connections it is just outside Montreal's economic orbit, while still-patchy broadband coverage also work against it. The county's unemployment rate is 1.5 percentage points higher than in Clinton, and 2.5 points above national average. Despite the abundance of good colleges and universities, graduates often leave because of the lack of opportunities. Census data show a net of 4,200 people left the county between 2010 and 2016.

Mairin Merna, a single mother from Ogdensburg, the county's largest city of about 11,000, said job prospects remained dim and would probably force her to move with her daughter to Albany, the state capital 220-miles away.

"Fifteen years ago I was more optimistic," said Merna, 34, leaving a one-stop career center in the nearby town of Canton, where she was among hundreds applying for local clerical work. "I don't know if there will be any change here," she said. "It's sad."

Reporting by Jonathan Spicer and Howard Schneider; Editing by David Chance and Tomasz Janowski