GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

The UK government is set to borrow billions of pounds from its emergency Bank of England overdraft to finance the fight against Covid-19.

The government will draw money from the Bank's "ways and means" facility to help workers and businesses.

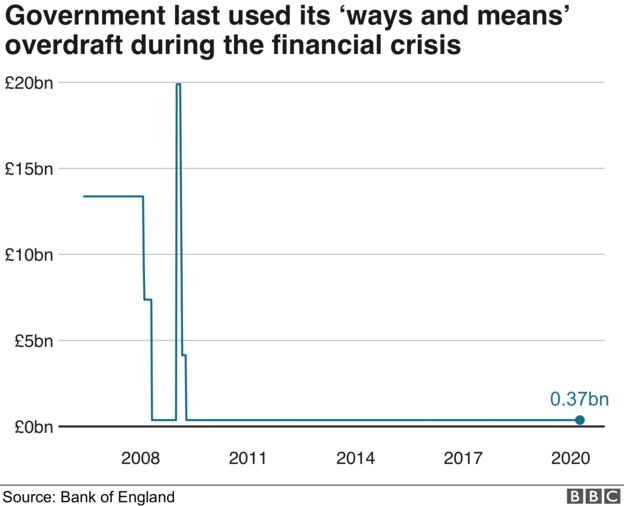

It has not used the facility since the financial crisis.

While it is controversial for a central bank to hand cash directly to the government, the Bank and Treasury insist the overdraft is temporary.

In the red

The ways and means facility will give the government a temporary cash buffer as it seeks to raise unprecedented amounts to deal with the coronavirus outbreak.

The last time it was used was at the height of the financial crisis in December 2008.

In normal times the government uses tax revenues to pay for public services such as hospitals and schools.

If there's a shortfall, it borrows the rest from investors by issuing bonds through the Debt Management Office.

But the government needs to raise a lot of money in a short period of time to pay for its economic stimulus package to support the economy.

It may run into funding problems if there aren't enough buyers for its bonds.

While the UK has not suffered a failed auction in the main gilt market since 2009, recent jitters in financial markets meant it couldn't find enough buyers in a short-term debt auction last month.

The ways and means facility gives the government the ability to get cash quickly while minimising any financial market disruption.

It is understood that use of the facility was agreed at the end of March, but strong demand for UK debt has meant it has not yet been needed.

The Bank will charge 0.1% interest on any money withdrawn from the facility. This is the same as the Bank of England base rate.

- Chancellor announces aid for charities

- Revamped loan scheme will make 'big difference'

- Government to pay up to 80% of workers' wages

In a joint statement, the Treasury and Bank said any use of the facility would be "temporary and short-term".

They added: "The government will continue to use the markets as its primary source of financing, and its response to Covid-19 will be fully funded by additional borrowing through normal debt management operations."

EU law prohibits central banks from printing money to directly fund public authorities.

Left unchecked, so-called "monetary financing" can cause prices to rise uncontrollably, like in Zimbabwe and Venezuela.

However, in the 1990s, Brussels agreed that the UK could maintain the ways and means facility until it decided to adopt the euro.

While the UK has since left the EU, the provision still stands today.

AFP

AFP

The move comes as the latest official statistics show that the UK economy was stagnant in the three months to February, just before the coronavirus pandemic escalated and lockdown measures were introduced.

The UK's gross domestic product (GDP) rose by just 0.1% between December and February, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said.

The ONS said: "Before the full effects of coronavirus took hold, the economy continued to show little to no growth."

Rob Kent-Smith, head of GDP at the ONS, said that the fall was down to wet weather and flooding seen across the UK hampering house building.

GDP fell by 0.1% in February, which was worse than expected. Economists had predicted that the economy would in fact grow during the month.

What happens next?

Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said that GDP could "fall at a speed and magnitude no-one has ever seen and no economy has ever experienced before."

Economic activity is thought to have slowed as social distancing measures have kept people away from offices, shops, cafes and restaurants.

Mr Dales added: "What happens next depends on how long the lockdowns last and how quickly households and businesses get back to normal.

"We've assumed a three-month lockdown. And while GDP growth would then surge in the months afterwards, households and businesses aren't going to be the same again for a while."

The Ways and Means account has not been used since the financial crisis, and is normally worth £400m. But outside experts say that this will increase by billions, perhaps tens of billions to help the government manage a sharp increase in immediate spending. During the financial crisis this overdraft reached just under £20bn.

It is also a mechanism to account for more direct lending of electronically created money from the Bank of England to the Treasury.

Over the past month there have been some periods of stress in financial markets for some forms borrowing by many governments. Right now, the Treasury is raising a record monthly amount of government borrowing, with auctions of debt on the majority of days.

This helps take the pressure off those processes at a time when tens of billions in cash is being handed out to businesses and to workers, and at a time when tax revenues are likely to stall alongside an economic contraction.

The government says whatever sum is borrowed will be repaid by the end of the year, and this is not a form of so-called "money printing".

But this is also the mechanism suggested by former top Treasury officials through which the Bank could more formally directly buy government debt from the Treasury, rather than buying it on the open market.

That has not been announced today, but is a possible consequence of the expansion of Quantitative Easing by the Bank of England announced last week.

Today's development is a sign of the unusual moves required to account for significant economic policy challenges around the pandemic, and a sign of things to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment