Nearly two years after presidents Barack Obama and Raul Castro announced a thaw in relations, Cuba’s communist government is turning to foreign investors to boost renewable energy as it faces cutbacks in cheap oil imports from Venezuela.

The government formed by Fidel Castro in 1959 and led by his brother, Raul, is pitching large wind and solar projects and biomass plants that run on sugar cane to foreign companies at conferences like one opening Thursday in Havana. The goal: Bring billions of dollars into sectors that until recently were controlled by state-run entities, and lift the amount of electricity produced by renewables to 24 percent by 2030 from 4 percent today.

The shift is less about ideology than supply and demand. The island nation relies heavily on oil-burning power plants that run on subsidized imports from Venezuela. With an economic crisis in that country threatening those supplies, Cuban officials fear a return to the turbulence of the early 1990s when funding from the former Soviet Union began drying up.

“It’s unprecedented for the government to be making an open presentation of this scale to international companies like this,” said Andrew MacDonald, director and vice president of Havana Energy, which is building biomass plants at sugar refineries. “This is a top priority for the Cuban government.”

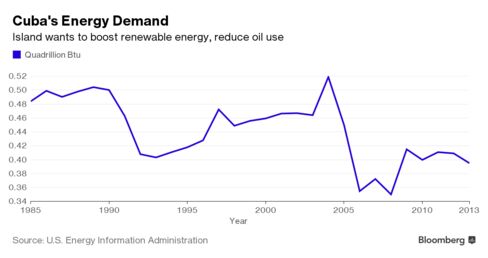

A decade-old initiative by Fidel Castro to improve energy efficiency and introduce renewable power has failed to reduce Cuba’s reliance on oil, natural gas and diesel fuel, which supply 95 percent of its electricity, according to a 2015 annual report from the government’s National Office of Statistics and Information.

A new goal to add 2.1 gigawatts of capacity from biomass plants, wind farms, solar projects and hydroelectric generators will cost about $3.5 billion, according to government estimates. To get there, Cuba recently said it will allow foreign companies in some circumstances to own projects rather than requiring them to form joint ventures with state-owned companies. The Obama administration has also carved out exemptions from a U.S. economic embargo to allow companies to export products and technology to the island.

“The opportunities there are huge,” said Bernardo Fernandez, Mexico director of operations for Hive Energy, a U.K. company that has agreed to build a 50-megawatt solar project in the Mariel Free Zone outside of Havana. “They don’t really need to attract anyone. They just need to clear the path for companies.”

Banking Challenge

Banking in the country remains a challenge. In June, Florida-based Stonegate Bank became the first U.S. bank to issue a credit card that can be used in Cuba.

“They have ambitious goals with respect to renewable energy and its going to involve heavy investment," said Lee Ann Evans, senior policy adviser at Washington-based Engage Cuba, a coalition of companies and organizations pushing to lift economic and travel restrictions. “It’s not as simple as replacing light bulbs.”

And, while Cuba also needs to reassure international investors, change is in the air. JetBlue flight 387 from Fort Lauderdale touched down in Santa Clara Wednesday, the first scheduled, commercial flight from the U.S. in more than half a century. Passengers included U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx, according to Cuban officials.

Oil Bounty

"Cuba needs to develop a clear plan for energy development that can serve as a guideline for investors," Ramon Fiestas Hummler, chairman of the Latin America Committee at the Global Wind Energy Council, said in an interview in Rio de Janeiro. "The country is changing its policies, but confidence still doesn’t exist."

Meanwhile Cuba, one of the largest beneficiaries of the late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez’s policy of sharing his country’s oil bounty, may be facing a reckoning. Under an agreement with Venezuela, Cuba receives more than 90,000 barrels of oil a day, which it partially pays for by sending doctors, teachers, and military advisers to Venezuela.

In a July address to the Communist party, Raul Castro said Cuba has seen "a contraction in fuel shipments" from Venezuela, without detailing the size of the cut. It had racked up about $15 billion in debt as of the end of 2015, according to a February report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

The circumstances have rekindled memories of Cuba’s so called Special Period, a euphemism for the economic crisis that began in 1989 with the breakup of the Soviet Union characterized primarily by oil shortages. The crisis led to the introduction of sustainable agriculture, the decreased use of automobiles and other industry overhauls as people were forced to live without many goods they had become used to.

"Cuba wants to open its frontiers," said Jean-Claude Fernand Robert, general manager for renewables in Latin America for General Electric Co. "The country still has a lot of work to do."

No comments:

Post a Comment