The more U.S. President Donald Trump strains the alliances that have sustained the post-Cold War order, the more indispensable Russian President Vladimir Putin seems to become.

By the end of Putin’s annual investment showcase that kicks off in his native St. Petersburg on Thursday, the leaders of four of the world’s 10 largest economies—Japan, Germany, France and India—will have flown into Russia for separate talks with the Kremlin boss within the course of a week. Putin will also host a new point man for foreign policy in China, Vice President Wang Qishan, and International Monetary Fund Director Christine Lagarde.

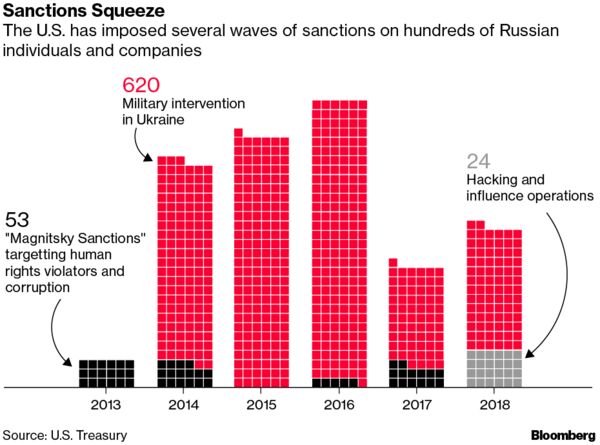

The highlight of the summits, Russian officials say, will be Putin’s meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron, the forum’s guest of honor along with Shinzo Abe of Japan. After years of sanctions over Ukraine, which Macron backs, and escalating U.S. penalties over alleged election meddling, Trump provided Putin an opportunity for rapprochement with Europe this month by pulling out of the Iran nuclear deal, angering other world powers.

“Russia is one of the main beneficiaries of Trump’s decision on Iran,” said Cliff Kupchan, chairman of Eurasia Group, a New York-based research firm. “Putin senses an opportunity to split the West and escape from pariah status.”

Putin, re-elected by a landslide in March, can boast of modest growth again after collapsing oil prices and sanctions imposed after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 triggered the longest recession of his 18-year rule. But converting geopolitical clout into badly needed foreign investment is a tough sell after the U.S. slapped unprecedented penalties on one of Russia’s largest employers, Rusal, severing billionaire Oleg Deripaska’s aluminum giant from global markets and hammering local stocks.

Trump and Putin in Danang, Vietnam on Nov. 11, 2017.

Photographer: Mikhail Klimentyev/AFP via Getty Images

Gone are the days when growth prospects for the world’s largest energy supplier lured corporate titans like Rex Tillerson, Jamie Dimon and Lloyd Blankfein to the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. This year’s program features only a couple of heads of publicly traded U.S. companies despite Trump’s newly arrived ambassador to Russia, Jon Huntsman, breaking with his predecessor by encouraging attendance.

While Russia’s economy expanded 1.3 percent in the first three months from a year earlier, the reading missed projections for the third straight quarter. The World Bank expects output to rise less than 2 percent a year until at least 2020, far below the level Putin needs to meet his goal of turning Russia into a top five economy by the middle of the next decade and bolstering stagnant living standards.

“Russia presents an interesting philosophical dilemma for investors,” said Tim Ash, senior emerging-market strategist at BlueBay Asset Management LLP in London. “The macro ratios—low debt, low deficit, current-account surplus—scream ‘buy,’ but nobody knows who or what will be sanctioned next.”

The Kremlin was relieved that Macron, a 40-year-old former investment banker who was born just as Putin, 65, was starting his KGB career, resisted pressure from allies to cancel his trip after Britain blamed Russia for the nerve-gas attack on a turncoat spy in England in March.

The accusation led to tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions across Europe and beyond, but those concerns have been overtaken by the Iran deal, which France, Germany, Russia and China are trying to salvage in the face of U.S. threats to ratchet up sanctions on Tehran and any companies that defy them.

Macron and Chancellor Angela Merkel, who flew to Putin’s summer residence on the Black Sea for talks last Friday, appear to be in lockstep on Russia. Macron told a French newspaper he wants “a strategic and historic dialogue” with Putin to tie Russia to Europe, while a senior German official said detente with Russia is now a core policy objective. The two countries are the largest sources of direct investment in Russia excluding tax-friendly havens like Cyprus.

Even as the European leaders remain at odds with Putin over Ukraine, Syria and other issues, the Iran crisis is pushing them closer together. At the same time, Merkel’s ties with Trump are deteriorating, with the U.S. now threatening to punish German companies involved in building a new pipeline for Russian gas under the Baltic Sea.

“In spite of everything that Russia does, Merkel has an interest in keeping that dialogue open,” said Josef Janning, head of the Berlin office of the European Council on Foreign Relations. And the more the trans-Atlantic relationship frays, the stronger her reaction will be, he said.

Putin, who hosted Narenda Modi of India, a major buyer of Russian arms, in Sochi on Monday, will anchor the forum’s plenary session on Friday, flanked by Japan’s Abe, Macron, China’s Wang and the IMF’s Lagarde.

Abe, 63, has been on a charm offensive trying to get Putin to strike a deal on a territorial dispute that’s prevented the two countries from formally ending World War II. He’s been stymied by Russian intransigence despite offering concessions and encouraging investment in the Pacific neighbor.

“The likelihood is that Abe will return disappointed,” said James Brown, an expert in Russo-Japanese relations at Temple University in Tokyo.

As for Wang, the St. Petersburg visit will be his first trip abroad since assuming foreign policy duties. Putin and Wang’s boss, President Xi Jinping, will meet in China early next month at the annual summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a security pact the two countries created with four former Soviet republics in 2001. India and Pakistan, arch rivals, joined last year.

But it’s Europe—and specifically Macron—that’s the focus of Putin’s attention this week. With no sign of Russia easing its involvement in Ukraine or support for Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, nobody expects sanctions relief anytime soon, but Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the Iran pact gives Putin an unexpected diplomatic opening.

And with Italy’s incoming populist government certain to block any new European Union sanctions and perhaps even trigger an easing, there’s suddenly a more “constructive atmosphere” for Russia in Europe, said Christopher Granville of London-based consultancy TS Lombard.

As a result, Putin will be able to tout this year’s forum as a success just by sharing the stage with the most high-profile attendees since Merkel headlined the event five years ago, according to Andrei Kortunov, who runs the Russian International Affairs Council, a Kremlin-founded think tank.

“It’s an important symbolic event that punctures efforts to isolate Russia,” Kortunov said.

— With assistance by Ilya Arkhipov, Patrick Donahue, Samuel Dodge, Gregory Viscusi, and Hayley Warren.

No comments:

Post a Comment