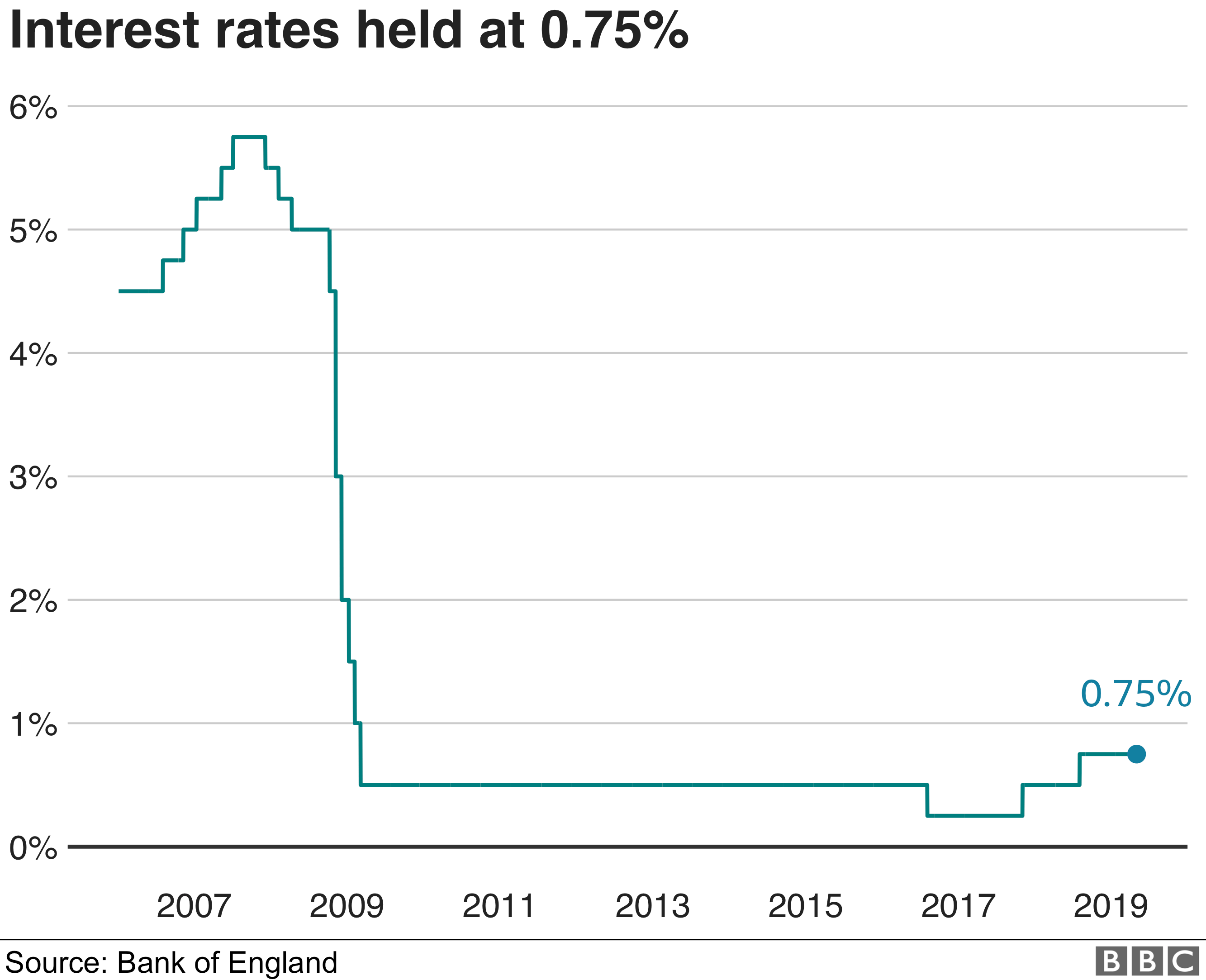

The Bank of England has held interest rates at 0.75% amid early signs of a pick-up in the UK and global economies.

In Mark Carney's final interest rate meeting as governor, the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted 7-2 to keep rates unchanged.

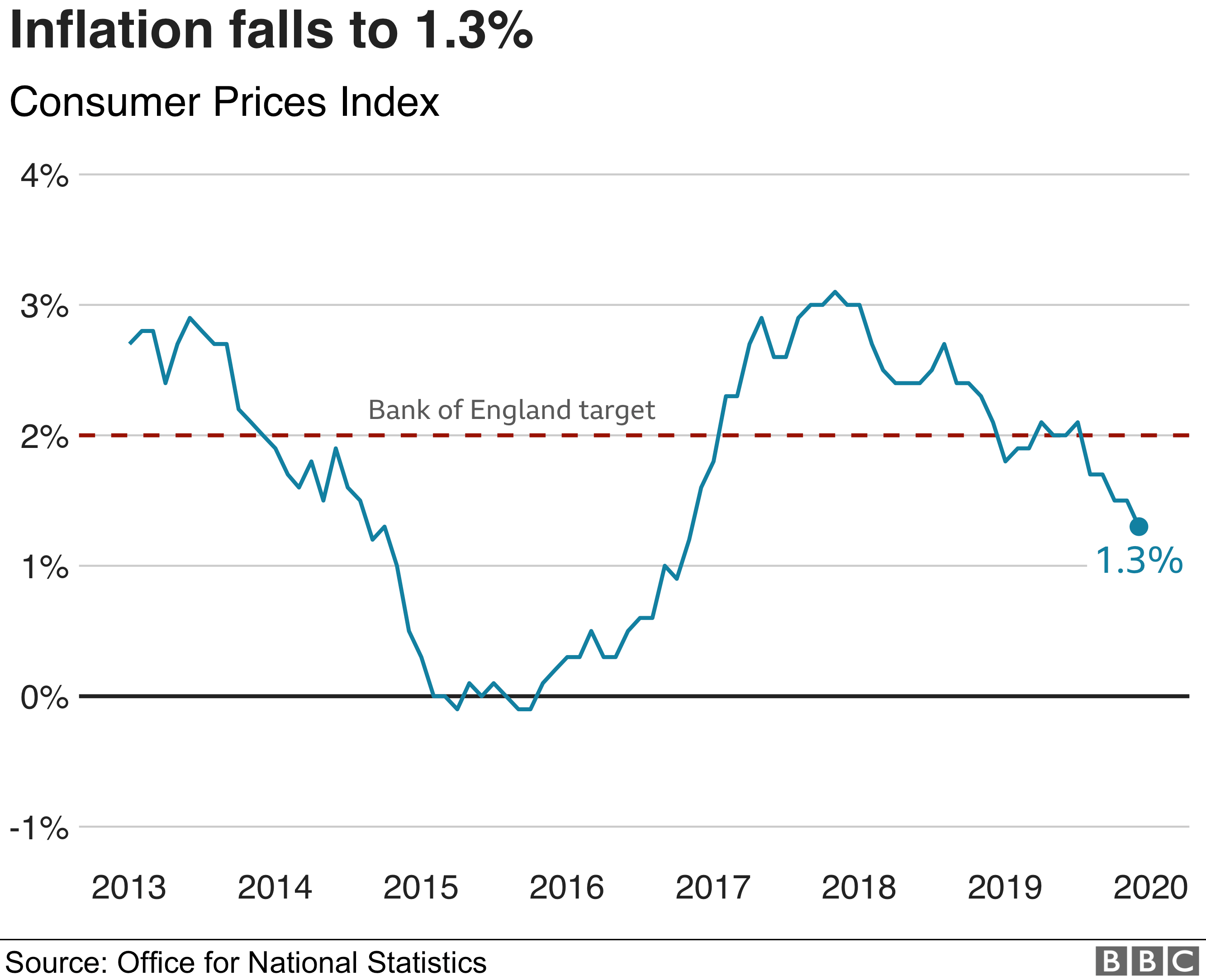

Recent weak economic data had led to speculation rates could be cut, but Mr Carney said "the most recent signs are that global growth has stabilised".

But the MPC said it was poised to cut interest rates if necessary.

Fewer companies in the UK are worried about Brexit, Mr Carney told a news conference following the rate decision. He added that survey data suggested UK growth will improve.

But he said: "To be clear these are still early days and it's less of a case of so far so good than so far good enough," he said, again referring to the UK economy.

"Although the global economy looks to be recovering, caution is warranted," he said. "Evidence of a pick-up in growth is not yet widespread."

He said the coronavirus outbreak was a "reminder of the need to be vigilant" when it comes to bumps in economic growth around the world.

Ready to cut

The nine MPC members have been split on rates since November.

Lower interest rates are good news for borrowers and bad news for savers because High Street banks use the Bank of England base rate as a reference point for many mortgages and savings accounts.

In a closely-watched decision, policymakers said they would monitor whether a recent improvement in business sentiment would lead to stronger economic growth.

The MPC said it stood ready to cut rates if there were signs that growth would remain subdued.

"Policy might need to reinforce the expected recovery in UK GDP growth, should the more positive signals from recent indicators of global and domestic activity not be sustained," the MPC said.

Two members, Jonathan Haskel and Michael Saunders, argued that past business surveys of economic growth had not been reliable.

They continued to call for an immediate interest rate cut to 0.5%.

Weak UK growth

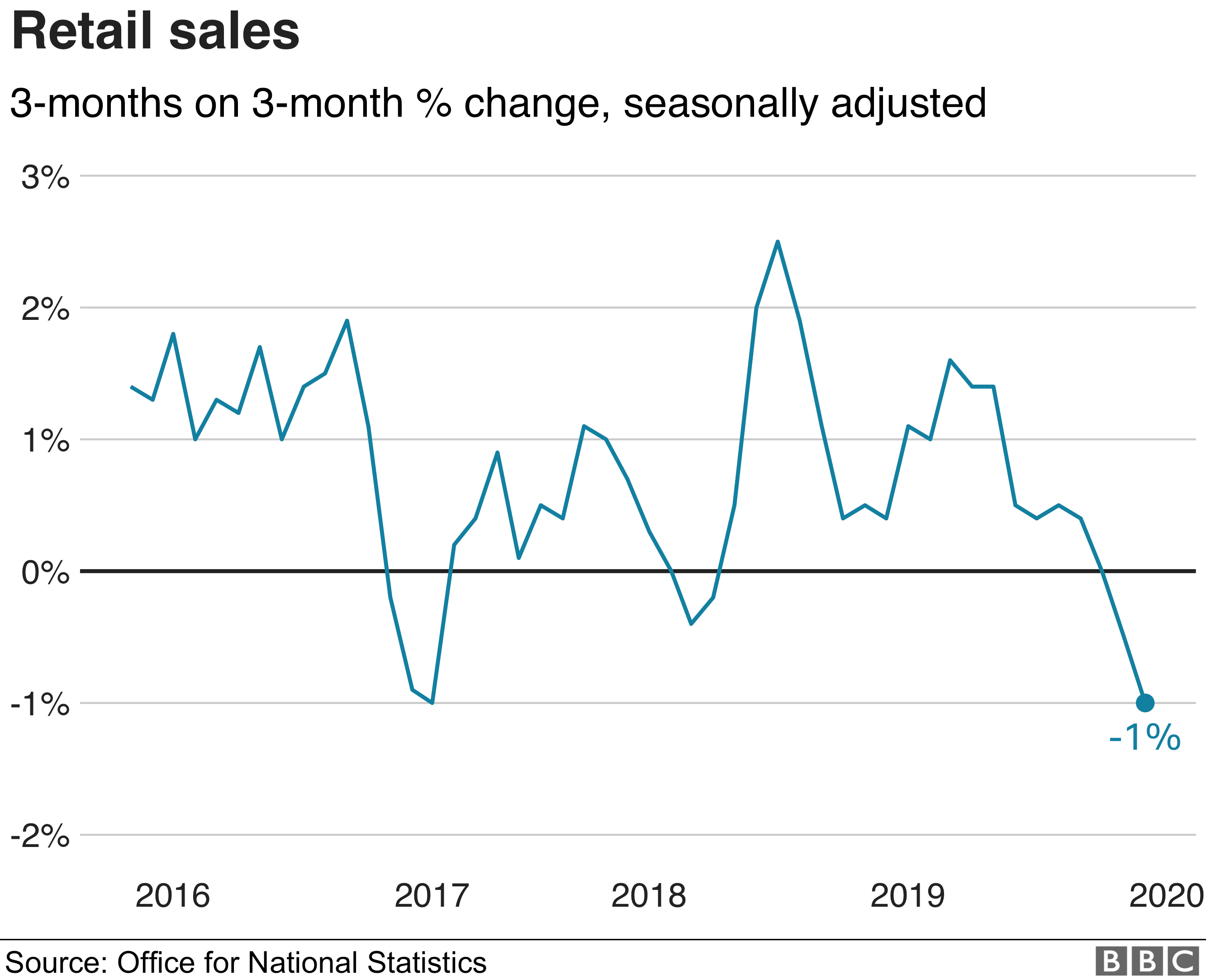

The Bank's latest economic estimates suggest the economy did not grow at all in the final three months of last year.

Weaker growth at the turn of the year is also expected to drag overall economic growth down to just 0.75% in 2020. This is down from a projection of 1.25% last November.

The UK economy is expected to expand by 0.2% in the first three months of this year.

The Bank said a trade deal between the US and China that lowers some tariffs would provide a boost to the global economy.

An expected rise in spending by the government in the March Budget could provide a further boost to growth, policymakers said.

Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, said she also expected stronger growth ahead.

"Admittedly, the MPC left the door open to a rate cut in the coming months, but with the economy turning a corner and a big fiscal stimulus approaching, we suspect the next move in interest rates will be up not down, albeit not until next year."

Brexit drag

The Bank said Brexit-related uncertainty had "weighed on investment" over the past few years.

Policymakers said companies' Brexit plans had diverted money towards preparing for the UK's departure from the EU that would otherwise be invested elsewhere.

This has reduced the UK's long-term growth prospects by limiting the space in which the economy can grow without the risk of overheating.

This would force the Bank to raise interest rates, which would in turn slow the UK economy.

Policymakers now believe the UK's potential growth has been reduced to 1.1%. This is down from 2.9% before the financial crisis and 1.6% over most of the past decade.